Jonathan Volk continues with Episode 2 of A Seat at the Table, looking at gaming’s obsession with serious, “complex” games. The first episode, “Playtime”, can be found here.

1. Serious Games Criticism

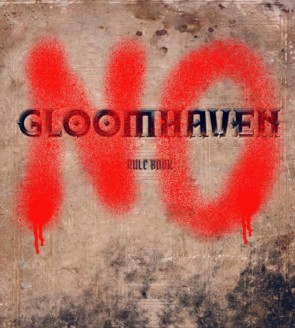

Is Gloomhaven the best board game of all time? No.

One thing I should mention: I have not played Gloomhaven.

#sorrynotsorry

Maybe I should back up a second to explain my criticism.

I take perverse pleasure reading the comments of online games criticism, where a certain kind of reader can usually be found screaming for a critical “objectivity”. Stick to the measurable facts of the THING, you weenie, these readers demand. It would seem that for many gamers out there, their chief interest in games criticism is reportage of the inarguable—that the thing is a thing; it is molecularly consistent, so far as we, those rare collections of idiot molecules that can talk about other molecules, can tell; gravity conspires against it in the usual ways; and its intangible qualities—mechanics, themes, narrative—are regurgitated to the reader in prayerful burps. The usual pathways of criticism have all but decayed, where someone (who we once unironically called a critic, replaced by one who we now unironically call an influencer) sits, for a time, with a cultural object to argue why said object demands (or doesn’t) others give up their precious time to it. Now, it is quite common for readers to show up to criticism already certain that the object, which they haven’t touched with their hands (nevermind their minds), is worth their time and, if the critic tells them otherwise, they demand the critic shut up and stick to the facts. Not only do we no longer want critics to do their jobs, we want to punish them for bothering to look for work in the first place. In this line of thinking, criticism is useful and virtuous only when it puts into words the thoughts we supposed we had, if we’d only bothered to put them into words ourselves. This hostility to criticism is like calling the fire department when your house is burning down and, as the fire fighters arrive, unspooling their hoses and aiming at the flickering calamity, propping their articulating ladder against the second floor window where you’re trapped and beginning to climb up toward the flames, and toward you, you give the ladder an evil shove. Who on earth has the nerve to not only tell you your house is burning down, but that they can save you from it? Just this month, in response to negative reviews posted about the first woman-led superhero movie from Marvel Studios, Captain Marvel, Rotten Tomatoes changed their policy of allowing users to review movies they hadn’t yet seen. Picture it: for years, anonymous “critics” had been logging in to praise or scorn the idea of a movie, an enterprise filthier than the floors of the theaters they weren’t even bothering to attend. Criticism is no longer the fallible attempt of mere mortals to say why grace is briefly possible. No, criticism has changed genres entirely, it is an outrageous saxophone anyone can pick up and blow having never learned to play the saxophone, but knowing that it, the saxophone, is the showiest, and likeliest, instrument to bring you attention. All that’s required is a capacity to blow. Sound and fury signifying a righteous nothing.

Where did the critic’s authority once come from? If you’re saying expertise, authority, years of work and toil—well, bro, how much do you lift? The Rock pours Rock-branded tequila into his oatmeal, and we realize we like to pour tequila into our oatmeal too. The influencer counts on the steroidal lift of his celebrity and, worse still, ruthless positivity, good vibes, the golden sheen of the piss he’s calling neu-water. And sites that feature (unpaid) user-generated content, unsullied by editorial gatekeepers, which include Amazon, Yelp, GoodReads, and, sure, RottenTomatoes, have made it possible for anyone to write and immediately publish thoughts on the best gastropub mac n cheese, the silkiest climbing chalk, why Thomas Mann is a boring idiot, and so on (confession: I live a second life reviewing climbing chalk). When everyone is an influencer with the Instagram followers to prove it, criticism becomes both a social expectation and a shameful liability—we’ve all got opinions just as we’ve all got You Know Whats, so don’t make me the asshole pointing out why you’re the asshole. In the race to dismantle the capacity for criticism to meaningfully dismantle why a cultural object does or doesn’t work (water is, dang dude, so primordial), we’ve also dismantled our capacity to piece together our own thinking with any coherence. We are broken shapes trying to point beyond our own brokenness, and I’m sorry, but I don’t, like, have the critical capacity to make that image clearer.

So why am I poisoning the criticism well, so to speak, and telling you that Gloomhaven, which I haven’t played, is not the best game of all time? As someone who has no strong desire to play board games like Gloomhaven with “automated” antagonists—should board gaming aspire to be greater than that solipsistic activity where you try to hit a tennis ball above the faded line of a rotted wooden wall?—you can take my no at the beginning of this essay for what it is: uninformed, pridefully ignorant, plain wrong. Maybe, after all, I’m part of this whole movement to render criticism meaningless.

Though Gloomhaven sits at number 1 on Board Game Geek’s influential, market-moving list of the best games of all time, I don’t see myself playing it anytime soon, and with a suggested list price of $140, it qualifies as “mass-market” entertainment the same way sky-diving does.

I presume most critics love these “best of” lists because they affirm our tastes or, even better, make clear who our enemies are. Seeing what strange things move others inspires a kind of critical rubbernecking, where I get to gaze luridly at someone else’s disastrous tastes.

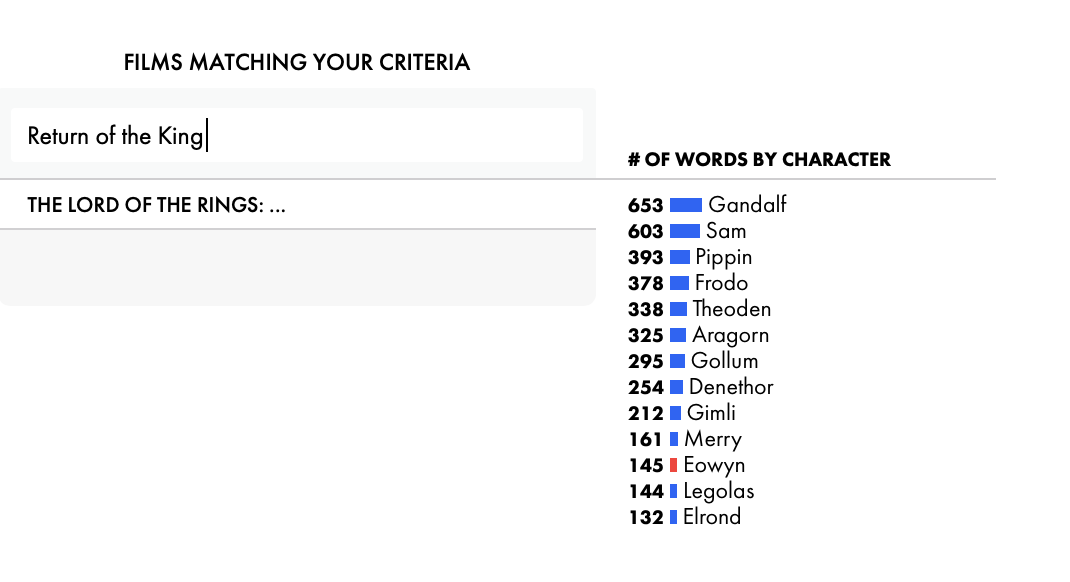

When I look at Sight & Sound’s poll of the greatest films of all time—regarded as the “serious” list, because it queries film critics and filmmakers—I feel a genuine shame for the gaps in my viewing, especially silent cinema (reader, I have not yet seen 1925’s Battleship Potemkin!). IMDb’s “Top 250” doesn’t inspire the same sort of shame, partly because its list more clearly announces the scruffy demographics of its voters: only one of the top 10 films, Pulp Fiction, can plausibly be said to have a female main character, while three of the films functionally have no women at all—Shawshank Redemption, 12 Angry Men, and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (Eowyn’s “I am no man!” is both an argument for and against the telling of her own story in Tolkien-land, where she ranks as the 11th -chattiest character in the film, saying 145 words total1; you could hire a pilot to sky-write all of Eowyn’s dialogue and probably still have enough money left to buy Gloomhaven).

Why do I feel shameful about my viewing gaps but not my playing gaps? Why does film inspire me to be a better filmgoer, which is to say to view more widely and with greater effort, whereas play inspires me to stick to the rolling provincialism of what I already know I like? Is it because film is obviously art, and art nudges us to scratch deeper at the confusion of existence, while play is, well, something lesser than or tangential to its arty roommate? If board gamers and game designers want to be taken seriously, how seriously should we critics consider the hobby? And if our most “serious” and influential board game critics are functionally sketch comedy performers in questionable costumes (Shut Up and Sit Down), or men wearing even more deeply questionable hats (Tom Vasel), should we abandon this conversation entirely and just, you know, play?

2. Serious Games

In “An analysis of board games: Part II - Complexity bias in BGG”, Dinesh Vatvani examines the “complexity bias” of user reviews in the Board Game Geek community. Accordingly, site users tend to reward games that have higher complexity ratings with, so it goes, higher overall ratings. The metaphor here is obvious: are more complex works of literature better than simpler works? I won’t make the case that War and Peace is “better” than Green Eggs and Ham, though I will point out that both consider oppositional binaries (maybe you don’t see green eggs and ham opposing one another, you say, I say, but just try them, I say, just try!). Tolstoy’s project is materially “more complex” than Seuss’s, as any readers who threw the book down during one of Tolstoy’s long and plotless chapters on historicity and the act of remembering can attest. I’m afraid that we are entering the listless land of subjectivity, that cruel place where war is better than eggs, to some critics, and I will relent. Certainly the metaphor is flawed here: if Gloomhaven is War and Peace, does that really make Codenames Dr. Seuss? Codenames is teachable within 5 minutes, as Seuss is readable in the same timeframe, but its complexities (and Seuss’s!) are emergent and largely social—you learn something about the ligaments of language, certainly, but also about the ligaments of your friends’ thinking, and the ligaments of your relationships to your friends. This should make sense to anyone who’s erupted at the end of Codenames that they have no idea how “submarine” is connected to the clue-word “schmear,” and the clue-giver’s cheeks turn the color of salmon schmear while they try to explain that, well, this, and salmon, you see, but…

Vatvani takes aim at the Board Game Geek Top Board Games List. Lovers of such lists know well the impossibility of comparison: how do I reconcile my love for Nancy Meyers’s The Intern with my love for George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road, both released in 2015? The guzzoline-whiffing post apocalyptic poetics of madness to cozy, encircling turtleneck domestic fantasias? They aren’t reconcilable, except that they are both movies, and movies don’t monolithically aim to do the same thing, besides dance light across a silver screen.

All that said, is Gloomhaven, currently ranked at number 1 on Board Game Geek, the War and Peace of gaming? Gaming’s The Shawshank Redemption (the best film, according to IMDb)? Or Vertigo (Sight and Sound’s top film of all time)? Or video gaming’s The Last of Us? These analogies might be flawed anyway because they operate under the assumption that board games are art, which we haven't yet determined; board games and other sports obviously contain artful elements, as a well-designed team mascot like Gritty can make a case for itself, but we’re not really habituated to think about sport and play as artistic. I'm going to get myself into trouble if I mention the balletic grace of Jordan dunking, or of Serena Williams serving, so I won't (forget it, reader). The blush of youth also seems to advantage games on the Geek list; chess, by comparison, has remained popular for 13 centuries or so, is teachable in 5 minutes, and emergently complex in a way that makes me dizzy (and whose complexities most of us will never be able to grasp), and yet it’s ranked down at 424.

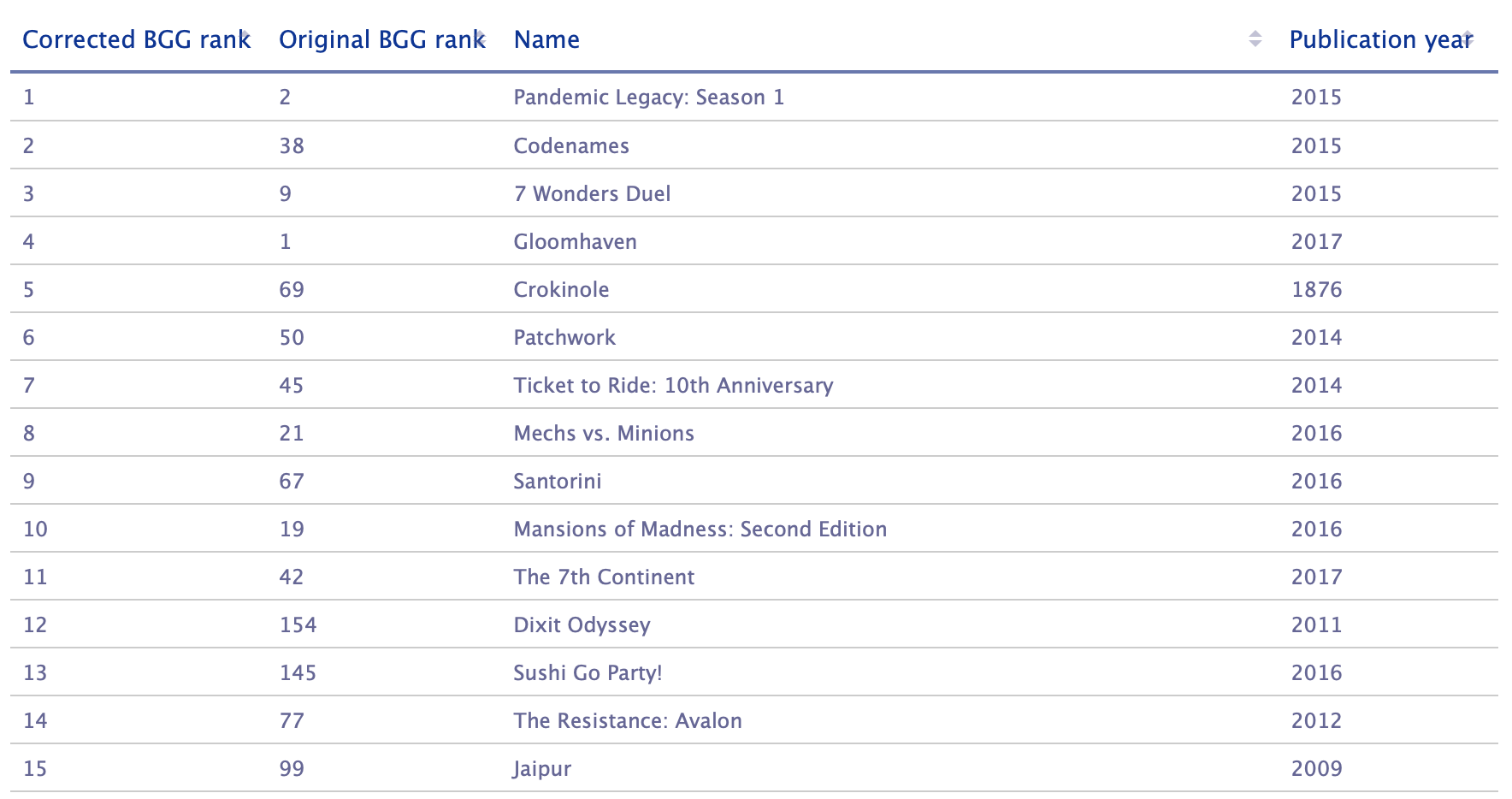

The value of Vatvani’s analysis lies in its “correction” of complexity bias. Vatvani gives us a very different list of the “best” board games once he corrects for this bias:

Crokinole, a game of finger-flicking pucks across a polished surface, moves from the deep 6os to the top 5. Conversely, Through the Ages drips through the rankings to 65. A Game of Thrones nosedives like a depressed child-king from 76 to 403. One Night Ultimate Werewolf gallops from its charming, if provincial, hamlet at 246 to the big city at 44.

Vatvani’s new list strikes me as a potential point of revolution for the game table, and demands that we at least begin to question how we usefully waste our time playing (and how we put an economic value to that playtime, afterwards). I can say outright I’ve had more fun playing Codenames (38—>4) than Terraforming Mars (6—>16), though I love both. Codenames is a hit no matter where I take it. Its universalizability shouldn’t be overlooked, whereas Terraforming Mars is a brain-burner with hideous aesthetics, its images a slur of competing graphic design schools of thought, crowding together sketches with clip-art with media commons photography. Asking people who have never played a complex game to play Terraforming would be like introducing cinema through Andrei Tarkovsky. A noble goal, maybe, but most of us didn’t fall in love with movies by watching miserable Russians wag their misery in silence through shots that go on the length of the Soviet regime. You see, our love of movies gets us to the miserable Russians, whose misery becomes for us, at least, another reason for living. But I don’t want movies to only do what Tarkovsky does, just as I don’t want board games to only burn my mind, or only deliver immediate, cool pleasure. (We can talk about pleasure in a later episode, which I’m already afraid won’t be pleasant.)

Better still, Vatvani’s list doesn’t shove complexity off the table entirely; rather, it argues that King of Tokyo’s (209—>40) chunky, nearly thoughtless dice rolls, which tell the story of kaiju wreaking chaos in Tokyo through gaming’s most satisfying and tactile chaos-manufacturer, the die, can clatter noisily across the same table as Eclipse’s cerebrally, arrived-at-through-complex-tech-tree-decision-making dice (27—>176). I don’t know if King of Tokyo is a better game than Eclipse, but I have some inculpatory evidence: I once taught Eclipse to a couple who, as the teaching ticked over the 1-hour mark, began to hold their heads as if they were trying to escape from the rest of their bodies. They were suffering deep into the playful mood, and that suffering tinged their strategies once the game finally started, each aiming to destroy the other. That couple went on to break up a month later, and I still maintain that Eclipse played a part in their dissolution, in all seriousness, because the collapse of the final ludic dartboard wall, Being Playful, can allow real suffering to rush in.

Chess, if you were wondering, actually falls from 424 to 1,684. Go, one of the oldest games we have, falls from 113 to 696. Both games actually score relatively high complexity ratings, even though they’re quick to teach, which sort of begs the question: what is complexity? Does it have something to do with emergent gameplay? The number of interlocking mechanics? Time to teach? Time to play? Time to master? Whether or not a super computer can beat me at it? (I’d love to see a super computer try to beat me at Dune.) I think it can be one or more or all, and that many Board Game Geek users might be describing the sheer quantity of stuff as complexity: consider, a pile of garbage might be more ‘complex’, materially, than a single page of Seussian poetry, but the Seussian page echoes a guiding, authorial complexity, a clean intelligence, that the pile of garbage never had, spoiled rotten as it is with stuff.

In the comments section of Vatvani’s article, some users are grumpily suggesting that Board Game Geek already has a way of “filtering” for an individual’s complexity preference. Don’t want to play a never-ending campaign of Gloomhaven? Click over to the Family Game’s list, you gentle idiot! But these Geek users are really arguing for the ghettoization of board games, a stay-in-your-lane dictate that diminishes what board games can and should do to a very narrow point.

Fine—but why do Board Game Geek users worship complexity above all other idols? I think part of their worship has to do with the anxiety of being taken seriously as gamers, which is mysteriously paradoxical. If we take away the older games, chess and go and poker, say, we’re left with a young medium, still in the “I DIDN’T ASK TO BE BORN” phase, and its relative immaturity expresses in ways that can turn off otherwise playful people, keeping them from the game table. There was a point in my early twenties when I craved complexity because I craved being seen as someone who was also complex. I proudly carried Infinite Jest on the subway, careful to hold the book open so that my hands didn’t obscure its title. The thrill of being seen doing something grandly complex by equally grandly complex people isn’t new or really at all impeachable—reading parlors used to exist precisely to allow readers to catch one another paging through an ever more fashionable way of being.

We construct our game tables as spaces similar to those reading parlors: we long for serious connection through the least serious means. And the broad cultural decay of serious criticism has done gamers no favors to help explain to others why our useless little pursuits actually matter. Let’s just not forget that we learned to read in increasing stages of complexity, just as we learned to play in increasing stages of complexity. That playful friend you love, who cracks you up with her refusal to ever be too serious, might really want to take a seat at the table, provided you don’t ruin it all with the rules of the game.

1According to The Pudding’s fascinating analysis of dialogue in Hollywood films: https://pudding.cool/2017/03/film-dialogue/:

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?