Beginning a deep dive into an all-time classic.

Chaos in the Old World (from here on out, CitOW) is an all-time classic that was one of the progenitors of the fusion of the vaunted "Euro" and "Ameritrash" styles of game and is easily in the running for the best game that Fantasy Flight Games has ever produced. That's a bold statement, but the innovation and solidity contained within its design support that assertion. It is clearly in the Dudes on a Map (DoaM) genre and borrows its setting and theme from one of the most Ameritrashy game companies ever (which is actually a British firm: Games Workshop.) But the focus on win conditions that don't necessarily involve outright conquest of your opponents, the tightly focused systems (especially the card play), and the subtleties of Domination and Corruption scoring are clearly drawn from the more mechanically-inclined end of the gaming spectrum. Despite designer Eric Lang going on to other regular successes (Blood Rage, Rising Sun, Ankh, etc.), it's difficult to look past the elegance and continued attraction of CitOW (admitted Slaanesh player here) as being a high water mark in his career. Every time I open the box and sort through the various Chaos cards, it's easy to imagine just how useful almost every one of them is and remember game situations where they were key to another classic session. It seems no coincidence that CitOW sits in a spot on my shelf on top of other classic games like Cosmic Encounter, the foundation of modern non-German game design, and Wiz-War, the inspiration for Magic: The Gathering and, thus, an entire genre of games. And, yet, CitOW doesn't quite hold the same status as those classics. Is it because it's out of print and likely to never return? Because it suffers under the onus of the cries of "Unbalanced!" and "Too random!" from those who never properly learned its nuances and strategies? Or is it just lost in the sea of stuff that is modern board gaming and which grows by literally thousands of releases every year? Maybe it's time to take a look and find out.

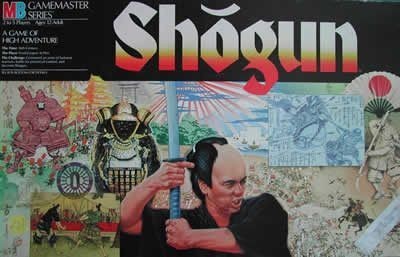

Physically, it's a mixed picture just like the fusion of its gameplay. Games Workshop had a prohibition in its licenses that forbade its clients from using minis in their productions that might encroach on GW's market. Especially in comparison to the modern market (not least many of Lang's releases), the figures in CitOW are acceptable but far from stunning. One of the most notorious aspects was the poor casting design for the Cultists which made the connection between their staves and the Chaos star atop them extremely weak, leading to a pile of multi-colored stars in the corners of the box and Cultists looking even more disposable than the gods already consider them to be. The contrast to that is the amazing artwork on the board, which is a map of the Old World on a sheet of human skin. I've long asserted that it's that innovation that led artist Andrew Navaro up the chain of authority at FFG to eventual head of studio. Anyone who understood the material and what his projects were about that well is someone who knows what they're doing, IMO. And it was important to know the material because, for the first time, a GW game had people playing not as the pawns of the Chaos gods or the opposition to their evil schemes, but as the gods themselves. This wasn't about deciding to play the good guys (Empire, High Elves, Dwarves) or the bad guys (Chaos Warriors, Dark Elves, Orcs & Goblins) in Warhammer Fantasy. You're the bad guys, full stop, and your object in the game is to finally fully corrupt the world and condemn all of its inhabitants to whatever misery most appeased the god you were playing. This was the contest of the four (and later, five) great Chaos powers writ large. That alone made it a draw to anyone familiar with any of GW's universes, since the Chaos gods extend from the fantasy Old World to the grimdark future.

But a great measure of the appeal on the mechanical side was that CitOW was one of the first significant examples of asymmetric play. That phrase has been abused in more recent times, such that some people think that any variation in player abilities (BoardGameGeek's "variable player powers") is an example of "asymmetric play." But that's an exaggeration of the type of approach that games like CitOW and Root truly embody. Two different clans in Rising Sun have different abilities but are, by and large, still trying to do the same thing. The gods in CitOW are actively trying to perform different tasks in order to achieve victory. You cannot play Khorne like Tzeentch and expect to win the game. They simply don't play the same way, but are still trying to achieve either one of two different ways to win: dial advancements or victory points. Now, there are clearly one of those two methods that a couple of the gods favor. Khorne will almost always win by dial ticks and Nurgle will almost always win by VPs. But Tzeentch, Slaanesh, and the Horned Rat are completely flexible in that regard in my experience, with the ability to flow with what other players have exposed and/or are permitting. One thing that really speaks favorably for The Horned Rat expansion (in addition to bringing a 5th player, another god, and my ever-favored ratmen into an active role) was the addition of new card sets for the four base gods that permitted them to push against those presumed tendencies and smartly expand the possibilities of an already incredibly tight design.

What highlights that design is the great balance between doing what you want to do and opposing what your opponents want to do. Everyone's goals are clear: Khorne wants to be in as many regions with as many opponents as possible. Nurgle wants to dominate (literally) the Populous regions. Tzeentch wants to be in Warpstone regions. Slaanesh wants to be in Noble or Hero regions. The Horned Rat wants to spread its Clanrats as widely as possible. Those are the basic tenets of the game. Power points have to be spent to summon figures to those respective spaces, but they also have to be spent to fill the two card spaces in each region in order to further your goals or counter your opponents'. With the Power economy as tight as it is (usually between 6 and 8 points), the limits on the number of figures and the limit on the game time itself (e.g. if you reach the end of the Old World stack, you lose to the benighted inhabitants of that world), every decision is important in every round. It's rare to find a German game where each and every choice will have ripple effects on both your play and that of your opponents. But this is still a half "Ameritrash" design, so there is variability that you and others will have to adapt to. Drawing the right (or wrong) cards may be key. Rolls of the dice, especially for Khorne, may be key. Whatever turns up in the Old World deck may be key. There are no routine or mundane rounds in CitOW. That can lead to more tension in a game than some will like, but I find it entrancing (Slaanesh!), not least because it means that even playing the same god in successive sessions will often be a wholly different experience.

Part of that is a consequence of the initial setup for at least Tzeentch, Slaanesh and the Horned Rat. Since the Warpstone, Noble, and Skaven tokens will be randomly placed, those three players will usually be honing in on those regions, respectively. If those regions happen to be Populous ones, they'll soon come into conflict with Nurgle. And Khorne will just be dropping in to where they think will be the easiest selection of targets, as they always act first in the Summoning phase. But the complicating factor there is that if, for example, the Noble tokens end up in Troll Country and the Border Princes, there won't be a lot of competition and dial advancement tokens should be easy to acquire. But it also makes that player an easy target for Khorne, whom we always referred to as "the sheriff", since they were the one who roamed the board looking to keep other players in line. All it will take is one dead Cultist in a region with two of them for Khorne to get a token and whoever the victim is to not get one. But beyond that, the hinterlands on the map also aren't worth much in terms of Conquest value. Certainly, making a run at a dial win is a primary strategy for four of the five gods, especially since doing so gains you benefits as your dial ticks toward final victory. But it's quite easy for VPs to explode in the later rounds, which means that you often want to at least participate in the downfall of the Empire, Kislev, Estalia, and so forth. I've seen many games where the Khorne and Tzeentch players were playing their own game and rushing toward a dial victory only to get overtaken by an opponent who made sure to corrupt the high Conquest value regions as much as possible and cruise past 50 VPs for the win.

The open information at hand is also extremely valuable. Unlike many other games of this type, the turn order is set in stone: Khorne > Nurgle > Tzeentch > Slaanesh > Horned Rat. That's the way the Summoning phase will be proceeding in every round, so you'll be able to properly anticipate how those before you will be acting. That's intelligence that in many games like this (The Hellgame comes to mind) offsets the "they got to go before me" factor. There's nothing a Tzeentch player likes more than watching what happens and then being able to respond to it more ably than almost anyone else. But everyone has that opportunity at some point. Likewise, when Battle and Corruption begin, the game follows a set path. You know how regions are going to be assessed and tallied from Norsca to The Badlands, every time. That definitely informs card play and actions like the Rat's ability to move their Clanrats from one region to the next right after Domination. Similarly, everyone's dial ticks are open knowledge. Veteran players will know what's coming up next and can use that information to adjust their play accordingly. While some might see the locked-in progression as a restraint, others will know that it's an opportunity to prepare for predictable moves.

But there's plenty of unpredictability, in addition to the random token placement in the setup; most notably in the form of the Old World cards. I've seen games where someone was instantly taken from a strong position to a middling one because of the turn of one Old World card that suddenly reset the conditions of the board. For many players, that's intolerable "randomness." For many others, that's part of the challenge of the game. After all, part of the theme of the game is the people of the world resisting the end of their world as they know it. That manifests most obviously with cards like Peasant Uprising, where all Peasant tokens raise the resistance of their region by one. But the emergence of cards like The Crusade is Come, Dwarf Trollslayers, and Divine Inspiration; all of which add Hero tokens to the board which remove figures in the End phase, can also have significant impact on the board where a single Cultist in a region going missing might disrupt long-laid plans for Ruination. As Khorne is often seen as the most implacable god, it's good to know that cards like Greenskins Invade and Electors Sue for Peace exist to limit the ability of combat to take place in various regions. But even the most indirect or widespread of effects like Meteor Showers, Up From Skavenblight, and Plunged into Chaos can have significant impact on the game because the system is wound so tightly. Suddenly, Tzeentch has many more options with more Warpstone in play or Khorne can gain a burst of points from a game of killing Peasants or Nurgle has an easier path to Domination because of Skaven tokens scattered across the map. But Warpstone helps Corruption plans and Peasants are easily gained by any god if they choose to move against them and Domination is also a path open to any god. And, again citing that wonderfully tight system, all of the decisions for the placement of these card effects fall to the player with the lowest Threat based on their dial. So, the player furthest behind the leader gets to decide random effects in their favor, keeping what is usually a close game even closer.

That's why even experienced players often opt to play without the expert-level Old World cards that came with the Horned Rat, as they have such far-reaching impact that they can feel onerous. Our group usually opted in, though, since we had refined our strategies to such a point that even having to deal with Resistance raised by two (High Elf Protection) or not being able to play cards without sacrificing two figures (Morrslieb Eclipsed) or paying more points for each figure and being limited to two dice per region (Vermin Outbreak) were just challenges that needed to be overcome. That's the same explanation I always used when describing GW games to people who disdained their primary engine: dice. The (ahem) chaos cubes do have a significant effect on this game and, yes, I have seen games where the Khorne player had a hot hand and ran away with it. I've also seen games where both Khorne and other gods balanced a win on a single roll of the dice and came away empty. The answer to both situations is to try to hedge the odds in your favor as much as possible, such that the die results will still have impact, but you'll have outs, as they say in card games. In almost every game I've ever played, dice are not a problem. They're a tool. If you can build your game around alternately minimizing and emphasizing their impact, then you'll be a step ahead of people who think they have "skill" in rolling them.

So as the title indicates, this is the first in a series. I've covered the general basis of one of the greatest games ever made and I'll be going into detail on each faction in the aforementioned turn order, just to make it easy. Next time, we stand before the sheriff and the Skull Throne.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?