I had my eye on this game for a very, very long time before I committed to buy. The reason was simply because if the legendary play time which gets attached to this monster. So, having taken the plunge, and played a few games, did I enjoy it as much as I thought I would, and did the play time issue matter as much as I thought it would?

A warning to readers – I purchase the expansion alongside the base game and every game of TI3 that I’ve played has used at least some of the expansion rules. It’s thus a bit tricky trying to give an entirely accurate review of the base game alone, but that’s what I’m going to try and do.

Rules

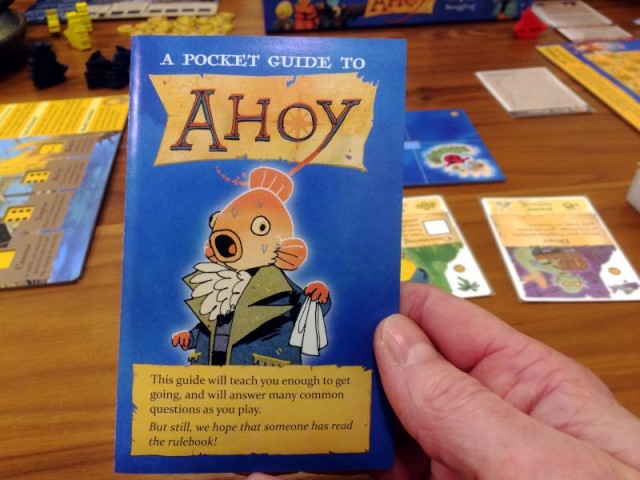

TI3 presents a fairly unforgiving face to those approaching it for the first time. The rulebook is large and fairly thick. It’s certainly complex enough to make summarising the rules difficult and therein is a conundrum: a summary is tough, but the length of the rules makes one especially important here. I’ve decided to try and approach this by focussing on what I feel the core aspects of the mechanics, the bits that make up the essence of interesting decision making in the game. Before I do that though, I must make an important point: TI3 is nowhere near as complex as it first appears to be. The rulebook is full of large diagrams, optional rules you need not bother with and flavour text but more importantly the rules are highly intuitive, especially for anyone with a passing knowledge of the sci-fi genre. The first pass through the rulebook is a longish slog but you’ll see what I mean as soon as you make the attempt: I found myself accurately guessing how parts of the mechanics yet to be introduced would work when only half-way through the rulebook. The game becomes even more intuitive during play: I know from experience that it takes no more than one game (in fact about the first 3-4 turns of one game) for people to become familiar with the rules.

The game proper is preceded by a setup phase. First, each player is random assigned one of the games’ races, effectively a parcel of variable player powers and setup positions to help keep the game interesting. Then the galaxy is created from a random selection of hexagonal system tiles which may contain planets, obstacles, wormholes (allowing fast passage from one wormhole to another) or nothing. The rulebook suggests this is done by players each having a hand of these tiles and taking turns to add one to the board. An extremely popular (and officially sanctioned) alternative is to use a pre-set map which reduces potential strategy in the setup phase but increases balance, decreases setup time and (arguably) increases the strategic interest in the game itself. Whichever option you choose the big imperial planet “Metacol Rex” appears in the very centre of the Universe.

Each game turn consists of three phases. The first is the strategy phase where each player picks a strategy for the round, indicating what strategic priority their race will be focussing on for the coming turn – technology, production, politics and so forth. There are eight of these strategies each one of which has a primary and lesser, secondary effect – we’ll come to how these are realised in a minute. Each also has a number which indicates play order for the turn – the person holding the 1 (“Initiative”) card goes first and then all the way down to the 8 (“Imperial”) card. Strategy cards which don’t get picked accumulate bonus counters making them more attractive in the following round.

The meat of the game is played out in a series of action phases, which come next in the game. The person with the highest strategy card number in play goes first. During an action round a player can basically do one of two things – play their strategy card or “activate” a system. Before we can launch into how these work, another of the central mechanics needs explaining – strategy counters. Each player starts with an assignment of strategy counters, more can be purchased during the turn and an extra two get doled out to each player at the end of the turn. Each counter is assigned to one of three areas – fleet size (the number of counters equals the maximum number of ships that player can have in one hex), strategy or command. The latter two get spent during the turn on the various action phases that come round, which is why more need to be replenished each turn.

When playing a strategy card, the player gets the primary effect on the card. The other players then get the secondary effect if they choose to spend a strategy counter to do so. Most of the cards do what they suggest – the “Technology” card for example gives players the chance to research new technology – the primary effect gives one for free and a second at a cost in resources, while the secondary costs anyone who wants to partake both resources and a strategy counter. Amongst those which require a more detailed explanation is the “Imperial” card – the primary effect of this reveals an objective (a goal to complete in order to get 1-2 VPs) gives the player 2VP instantly – 10VP is the usual goal to win the game. Also of note are the “Trade” and “Political” strategy cards which are designed to introduce greater levels of negotiation into the game, through striking trade deals and building support for voting on laws respectively. When you choose to play your strategy card amongst your other action phases is often a key strategic decision.

The other – and much more frequent – action you can take is to activate a system. To do this you sacrifice a command counter from your allowance and place an activation token on the system you’re targeting. You can then move in spaceships which are eligible to move. If there are enemy ships in the system then a battle ensues, otherwise you have an immediate choice as to whether you want to drop any troops being carried with your ships onto planets in the system. If you do, and the target planets contain enemy troops then it’s battle time again. Otherwise you get them unopposed. Finally you can build things in the system – if there’s no Space Dock you can build one, otherwise you can build new ships and troops at an existing Space Dock. When building things you pay with resources which are gained from planets – you can “exhaust” a planet to gain its full resource value during a build and excess points cannot be saved for later. They key point about this slightly bizarre system is that you cannot activate a system twice, nor can you move ships out of a system which has already been activated. Thus it neatly ensures that ships can only move once a turn and planets can only build once a turn whilst making the decision of what to activate in what order for best effect an interesting one which combines min/maxing with strategic considerations.

Each turn then ends with a bookkeeping phase. Various things happen here such as the distribution and rearrangement of strategy counters, exhausted planets get refreshed and so on. However, the key part of this phase is that objectives can be claimed. The objectives on offer vary greatly from combat based ones (defeat an enemy fleet containing at least three ships), conquest based ones which can sometimes be completed bloodlessly (conquer two planets this turn) civilization based ones (get three tech advances in one colour) and sacrificed based ones (pay ten resources) and the set used changes each game, keeping up the variety. It is important to note that there is a very popular optional rule (the “Age of Empire” option) regarding objectives in which 8-10 objectives are laid out at the start of the game and a player may claim one during each bookkeeping phase. Proponents of this rule state that it makes the game faster and more strategic because you can plan in advance which objectives you’re aiming for. People who prefer to play without this rule feel that the original rules force you to keep a balance, ready to claim any objectives as they come up. Which you prefer depends entirely on your play style. Personally I don’t see any reason not to play with the optional rule in force, because I prefer the level of planning and strategy offered by the variant and because I fail to see what needing to keep your play style in balance could really add to the game. In the remainder of the review, unless stated otherwise, I’m describing the play experience as it occurs with this optional rule in force.

And that’s it, in a fairly large nutshell. There are other supporting systems of course – there are action cards that can be gained and used to help your progress or hinder those of other players. There are various technology trees that can be followed which open up new powers and thus strategic possibilities. There are a variety of ship types of course, and the combat rules which see all ships firing rolling a d10 versus a number dependent on the ship type. That’s pretty much the only dice rolling that occurs in the game and in general there’s less random content than you might think: even the vagaries of combat can be minimised through wise fleet building and target selection.

Gameplay

Twilight Imperium 3 falls into my favourite category of games, a category I loosely define as “multiplayer conflict games”. As well as sharing a distinctive group of features these sorts of games also tend to come with a fairly distinctive group of problems: kingmaking, kill-the-leader and the potential for the diplomatic meta-game to trump any sort of strategic decision making in the game, such as the situation when both your neighbours on the board decide to join forces and kill you. I usually enjoy these sorts of games in spite of these flaws, but I’ve always been on the lookout for games of this ilk which mange to overcome these inbuilt problems without resorting to simply restricting the ability of players to do this if they choose. The first I found was Titan. TI3 is the second.

The core of TI3’s success in getting over these obstacles is the impressively varied objective system which works through the very simple expedient of not granting points to people who choose to indulge in, well, kingmaking, kill-the-leader and neighbourhood disputes. It is aided and abetted by the board layout which tends to encourage conflict at the centre between everyone rather than between neighbours. If you want to join forces with someone and beat the crap out of a mutually adjacent player then you can – but it’s extremely doubtful you’ll gain any significant advantage by doing so. This doesn’t mean that diplomatic bargaining and backstabbing aren’t an important part of the game, because they are. Rather they are forced to sit alongside other strategic considerations instead of having the ability to dominate everything. Rather, through the mechanism of having varied objectives that require expansion, control of resources, control of the centre (the planet of Metacol Rex) and other things as well as simple conflict the game rewards players who seek a balanced approach to building an intergalactic empire, and a clever player can avoid the kill-the-leader scenario by planning where he’s going to get his last VP or two from before he launches the bid to take the lead.

Which brings me nicely on to the second point: this game feels, and plays, more like a science-fiction civilisation game than it does a particularly intricate game of resource control, unit purchase and conflict. Again, that objective system which covers such a wide range of goal types is partly responsible for this. The length helps – this is a game with will take 1-2 hours per player to complete. Many people complain about the length making the game unplayable but there is a very simple fix: play for less victory points and besides, complaining about length in a game of this nature is a bit like complaining that chillies are hot. Without the length the game would loose some of the epic feel that graces it, and indeed in honesty, if it were easier to organise and host a game it would loose more of the sense of it being a special occasion. The final piece of the civilisation jigsaw is the way the game, having used the objective system to push the diplomatic aspects of the game into the wings, uses the Trade and Politics strategy cards to drag it right back out again and make your galactic empire feel like a proper galactic empire with commerce and intrigue sitting alongside essential elements of exploration, warfare and scientific advance.

The Trade and Politics cards deserve special mention because although they’re clearly and obviously attempts to bring negotiation back to centre-stage without letting it ruin the game, they don’t entirely succeed. In politics a political agenda card is drawn and the assembled players must vote yes or no to the proposal using the influence values of un-exhausted planets. The idea is that the players who have most or least to gain from whatever the agenda is should attempt to persuade, with threats and bribery if necessary, other players to throw their votes into their camp. In practice what usually happens is that players either vote individually for whatever suits their position best or that the person holding the strategy card times his play so that he’s the only one with significant un-exhausted influence and thus can control the vote. The trade round, in which players negotiate trade contracts, is more interesting, not least because trade contracts can be broken in war so you have to be careful who you end up exchanging contracts with! However, the player who played the Trade card gets to have final approval on all negotiations. So again, in practice what usually happens is that the players have a Trade deal imposed on them by the active player, and it’s usually one that’s fairly balanced but which hands a slight advantage to the person approving the deals. Furthermore, once in place, these contracts don’t tend to change that much over the course of the game.

Some people might be surprised to learn that this seems to me to be a game which rewards clever tactics and long-term strategy far more than other elements of the game. We’ve already discussed how the potential beast of the meta-game is held in check without being eliminated from proceedings. There are random elements to the game of course and good job too: they add exciting and memorable moments to the play whilst rarely being allowed to trump a well planned strategy. Dice are only used in combat, which is only one part of the whole picture and combat is conducted in such a way that you can take out much of the danger of poor rolling through proper fleet composition – but not all the danger else it would quickly become sterile. The randomness of starting hands of tiles right at the beginning can be unfair but this is easily ameliorated by using a pre-set map. The other main area of randomness is doling out action cards but it’s usually the way you choose to use these cards which is key, rather than the variable power of the cards themselves. Besides, if you don’t like your hand the game offers various race- and technology-related means to recycle what’s in your hand. What’s left is a dizzying array of interlocking strategic factors to pull into place – what strategy card to choose this round, which objective(s) to go for, what systems to move in and out of, where and what to build, who to attack, how best to spend the resources from your (non-divisible) planets, how to distribute and use your command counters, which strategic secondaries to invoke and so on. The game also places good timing at the heart of good strategy – oftentimes I’ve found myself puzzling over what order to take various actions I need to take during a given round. There are various aspects to this – the requirement of not being able to move craft in or out of activated systems being one, the good timing of your strategy card being another. For example if you hold the Logistics strategy, which offers bonus command counters as both a primary and secondary ability, it often pays to play it as late as possible to see if you can get some players to run out of counters and pass, putting an early stop on their activities in the turn. But of course you also need command counters to continue – so when is the best time to activate and how can you spin out your turn for as long as possible without invoking the card? TI3 is generally regarded by long-time players as being a game in which the same players can triumph over and over again – and what surer test is there of the strategic depth of a game than that?

One of the great things about TI3 as a whole package is that the game is stuffed to the nines with variations and optional rules many of which have a serious impact on how you go about formulating a strategy to play. A good proportion of the different races have a special ability which breaks the game rules in fundamental ways and allows you to try out new tactics. Sol, for instance, can spend counters to spawn new ground force units and this frees you from your reliance on Space Docks to build forces, allowing you to expand and consolidate in new ways. In the optional rules basket you’ve got Leaders, new unit types with special powers that will change the way you build your strategies, and Distant Suns, an option which places a premium on fast expansion and exploration over defence and again brings new situations into the game that require new plans to exploit. The scale of these possible combinations is staggering and as a result the potential replay value of the game is huge.

Criticisms

It should be pretty obvious by now that I’m a fan of this game. In the interests of trying to present a balanced view for people assessing whether to buy this game though, let’s take a look at some of the common complaints people have about the game.

The first is the length. We’ve already covered that one, but it’s worth a reminder that if you find the game too long you can shorten it by playing to less VPs. So I’m happy to dismiss this as an issue. This is worth playing when you get the chance, even if the chance comes up only rarely. A related issue is complaints about significant player downtime which I find slightly bizarre since in my experience the quick-fire nature of each player taking a turn to complete a short action phase leads to entirely acceptable levels of downtime.

The most common complaint aside from the time seems to some variation on the theme of there not being enough conflict, or that the game encourages “turtling” (defensive buildups) or that not enough meaningful actually happens during the game to make it worth the time investment. The former two of those points are entirely true and they make a serious point which I’ve already tried to cover – this is not a battle game. If you came here expecting a battle game you’ll be disappointed so go get one of the many excellent sci-fi battle games on the market such as Nexus Ops. This is a civilisation game and if you approach it from this angle these “problems” disappear and become a benefit – part of the epic feel of playing the game. The one about meaningful actions is a little harder to pin down, but I assume that by “meaningful” the critics mean actions that advance you toward the goal of gaining VPs. In the core rules as written this certainly is a problem, although one I find decreases my enjoyment rather than ruining the game outright. However there is a simple fix – use the “Age of Empire” variant from the rules which lays out all the objectives right from the start and you’re in to long term planning and meaningful decision making from turn one. That’s the reason this variant is so popular – and indeed I’m somewhat surprised it isn’t part of the core rules, with the slow revelation of objectives being the variant.

The other big complaint is about the nature of the Imperial card. Basically the automatic award of 2VPs is so important that you can’t afford to pass up any chance you get to take this card. This leads to a situation where a player picks the Initiative card (giving him first pick next turn) and then picks the Imperial card and then the next player round the table does the same and so on, considerably reducing the strategic variety in the game. Worse (in my opinion) it has the potential to create anticlimactic ends based on lucky timing – whoever is next in line for the Imperial card wins the game. The card was clearly designed as a timer, injecting a regular dose of VPs in the game and forcing out a new objective every turn but in frank honesty, I have to concede that it can spoil enjoyment of the game. However, yet again there is a simple fix – FFG have released a variant Imperial II card which is official, free to download and works very well. This card grants you one VP for being in possession of Metacol Rex and allows you to qualify for multiple objectives which manages to solve the problem whilst keeping a reasonable (if slightly slower) flow of VPs into the game and has the pleasant side benefit of increasing the amount of conflict in the game. You’ll have to print out and mock up the card yourself which spoils the look of your game rather, but this is a minor price to pay.

I have a couple of niggles of my own which don’t actually seem to get mentioned that often by other people. Firstly, although the various mechanics and strategies in the game do interlock very well, the designer has clearly drawn on so many varied sources in order to get the effects he wants that the result feels strangely cobbled together. Secondly, and this is a pet peeve of mine, the game has obviously been designed from a six-player standpoint and doesn’t scale brilliantly - the other supported player numbers are certainly fun, but six is definately best. With five it’s imbalanced for three of the players, although there’s a somewhat bizarre pre-set map to fix this. With four each player takes two strategy cards and you use all of them every round which removes the potential interest of bonus counters and forces some players into highly suboptimal choices. With three it plays pretty well as a combat and resource management game but, for obvious reasons, looses much of the pleasure derived from negotiation.

The Expansion

I wrote a separate review of the expansion, which you can find here. I thought it worth including here since it’s so often seen as being essential to the point of it being worth buying both at once. My conclusion in summary is that although the expansion is very good, has the potential to speed up the game and fixes most of the problems that have been perceived with the base set, it’s not actually essential.

Conclusion

Twilight Imperium 3 is an immense, epic, monster of a space civilisation game that manages to brilliantly balance a large number of aspects of play into one pleasing whole. When I was younger and used to sit for hours playing multiplayer conflict titles such as Risk and Warrior Knights I used to dream about someone designing a game like this. Now someone has and I only wish I were back in those younger days so that I had the time to sit for hours playing it!

Giving the base game a rating is difficult. I’ve never played it without the expansion for one thing. The other issue is that out of the box the game does have significant problems – the Imperial card is an unpleasant carbuncle and the objective system as suggested in the base rules does mean you can end up floundering around for significant periods without actually achieving anything. I’ve always argued that not presenting a game properly in the first place is a definite flaw, and that releasing later variations, no matter how easy to implement or successful they are, isn’t much of a solution. So as together my own minor dissatisfactions with scaling and such, I’d give it a seven. Using Age of Empires (which is at least in the rulebook) and Imperial II (which is more obscure) would add a point each, giving it up to nine. Played with the expansion it gets the full ten.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?