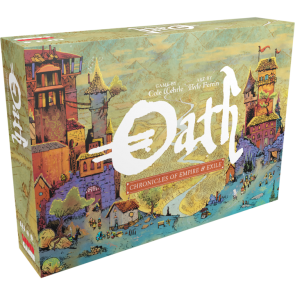

Oath creates a grand narrative. While I believe it will develop an extremely devoted following among players who brave several plays and are not averse to the traditional characteristics of the multiplayer conflict genre, it is going to fall flat among many of the people designer Cole Wehrle brought onboard with his much more approachable Root.

It is unusual to review a game before it is released, but it is also unusual for a team to do almost all of its playtesting online and provide a feature and art complete tabletop simulator module well before the physical game is released, as Cole Wehrle and Leder Games have done with their newest kickstarted game, Oath. I’ve played enough, around twenty-five times, to feel comfortable with a pre-release gameplay review in order to let you know what to expect in spring when it is physically released.

Fundamentally, Oath is a multiplayer conflict game in the vein of Chaos in the Old World, Cthulhu Wars, or Lords of Hellas, but one that has a player pawn focal point and somewhat deemphasizes holding territory. It also adds a unique persistent element across games, the Chronicle. Each player’s goal is to seize one of the four objectives, determined at the beginning of the game, long enough to win the game. An incumbent regime player starts with advantages already in place (the Chancellor) and the game will quickly become complicated by the introduction of various “Visions” entering the game that present other victory conditions to the non-Chancellor players.

Instead of providing its special powers via differentiated plastic units (e.g. Kemet) or innate player power boards (e.g. Root), at the heart of Oath is an enormous deck of around 200 cards (“denizens”). In a single game, you will only have 50-60 of these cards available, describing the major features of the current world, and will almost certainly see only 30 of those cards each game. These cards are all completely unique, providing military, mystic, political, and even more niche and bizarre support to the players in their struggle with one another. The suited world deck serves to shape player incentives and specialties. While some cards are relatively mundane, giving bonuses to combat or other marginal changes, other cards reshape the context of the game in its entirety and the design team clearly felt no compunction to keep their ideas within a carefully bounded box.

Where Oath succeeds in spades is in providing drama. Because of the cornucopia of special powers, which are not afraid to be game changing, games will generally hinge on critical plays featuring the deployment of wild special powers. There are cards in the deck which make a player impossible to target via military campaigns, that force a player into the Chancellor’s existing empire against its will, and that make binding deals, even across games, possible. While some of that incredible drama is random and tactical, via pulling out a single lucky card, most of the drama I have experienced among skilled players is strategically coherent: players carefully build up a plan through several turns of card draws and preparations, then unveil that plan in a gamble on victory while their opponents do the same.

The narrative momentum Oath builds is enormous. I suspect, however, that this narrative will not resonate with players who describe themselves as narrative or thematic gamers, as none of the narrative is provided by flavor text or executive direction from a scenario or faction designer. It is instead generated mechanically, via minimalistic card titles, weird art, and strong card suit themes. Expanding this narrative focus through mechanics is the Chronicle system, which has the winner of a game add new cards into the world deck from the suits they used to win from the massive card sideboard, then removing other cards of other suits back to the box. Individual games of Oath are most akin to a dramatic short story in the much longer book of a fantasy world. Over many games, the entire game state takes very distinct thematic states due to its denizen card balance and how dominant the previous win was by the incumbent. A “Discord” suited world, where many players have been winning using discord cards in previous games, focuses on stealing from other players and burning the economy of the game to the ground while an order suited world is focused on site control and military dominance. Over time, the legacy element enhances the game an enormous amount, to the extent that a friend I play with in our forums has called the sequence of games in a continuous Chronicle “the real game.”

As the follow up to the Wehrle mainstream hit of Root, Oath superficially seems to hit some of its notes, especially its focus on player powers and troops on a map structure. Several plays, however, will reveal that Oath is something far different, to many people’s dismay and my delight. Oath is larger and much more ambitious, a completely open sandbox. This is incredibly intimidating to new players, and I suspect will lead to some extremely poor first and second impressions from excited Root enthusiasts, especially as their games run agonizingly long. Because Oath presents you with six action options and features 30+ special powers entering play throughout the game, it provides a dismaying array of options that will drive even non-analysis paralysis players to a grinding halt. This is particularly problematic because Oath features game mechanics which generate a tremendous amount of frustration in a very long game, including an unforgiving zero-sum economy, kingmaking opportunities, large swings of fortune due to the introduction of new special powers, and elaborate deal making. Oath is a game that wants to be around two hours or less, which is easily achievable with experienced players, but takes an agonizing three to four on first plays because its rules are quite crunchy and it has so many unique powers. Oath also wants players to play multiple times and observe the changing texture of the world being built, along with the new, more radical, cards being added to the world deck. But multiple plays with the same players of a game with kingmaking is not in the cards for most modern board gamers; I think Oath is doomed to be a niche success compared to its more on-the-rails, curated, cousin, Root. Ultimately, though, I believe that Oath will develop an extremely devoted following among players, like myself, who brave several plays and are not averse to the traditional bugbears of the multiplayer conflict genre.

As the follow up to the Wehrle mainstream hit of Root, Oath superficially seems to hit some of its notes, especially its focus on player powers and troops on a map structure. Several plays, however, will reveal that Oath is something far different, to many people’s dismay and my delight. Oath is larger and much more ambitious, a completely open sandbox. This is incredibly intimidating to new players, and I suspect will lead to some extremely poor first and second impressions from excited Root enthusiasts, especially as their games run agonizingly long. Because Oath presents you with six action options and features 30+ special powers entering play throughout the game, it provides a dismaying array of options that will drive even non-analysis paralysis players to a grinding halt. This is particularly problematic because Oath features game mechanics which generate a tremendous amount of frustration in a very long game, including an unforgiving zero-sum economy, kingmaking opportunities, large swings of fortune due to the introduction of new special powers, and elaborate deal making. Oath is a game that wants to be around two hours or less, which is easily achievable with experienced players, but takes an agonizing three to four on first plays because its rules are quite crunchy and it has so many unique powers. Oath also wants players to play multiple times and observe the changing texture of the world being built, along with the new, more radical, cards being added to the world deck. But multiple plays with the same players of a game with kingmaking is not in the cards for most modern board gamers; I think Oath is doomed to be a niche success compared to its more on-the-rails, curated, cousin, Root. Ultimately, though, I believe that Oath will develop an extremely devoted following among players, like myself, who brave several plays and are not averse to the traditional bugbears of the multiplayer conflict genre.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?