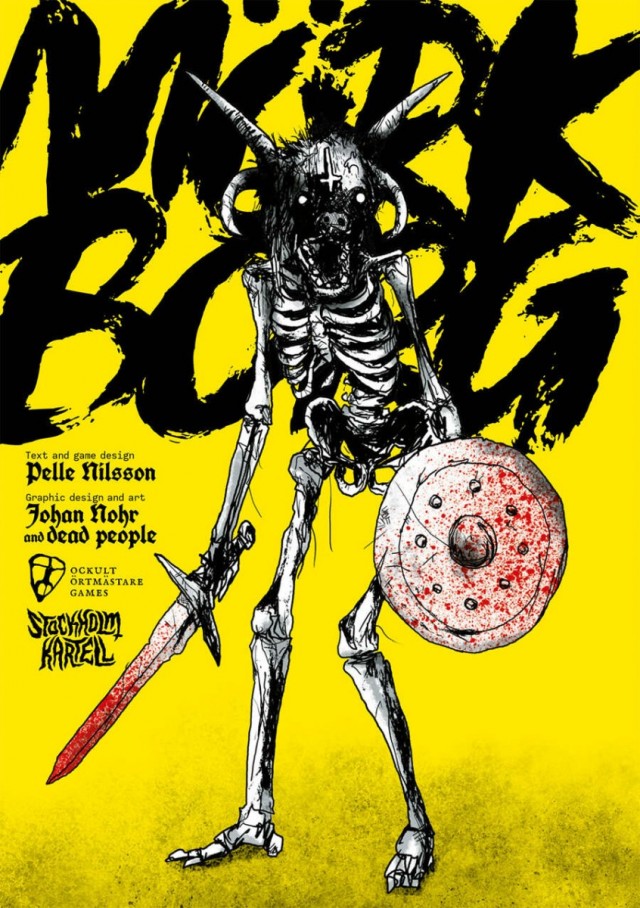

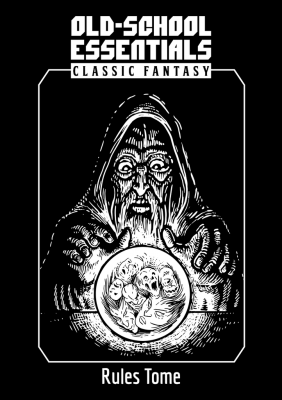

Recently, I had the pleasure to do an interview-based feature on the Old-School Renaissance in role-playing games for Dicebreaker. As part of it, I got to interview the designers of two of the biggest games in the movement, Old School Essentials and MÖRK BORG.

For the introduction to what we’re talking about, please go read the original piece. All the people I talked to were loquacious in their enthusiasm for these games, and I had a ton of great interview material to use. The best quotes made it into the feature but, due to time constraints, I had some left. Here they are, in Q&A format, for your enjoyment.

The first interview was with Gavin Norman, whole cleaned up and re-organised the D&D B/X rules for Old School Essentials, which I reviewed last week.

TWBG: What would you say to players whose neophyte characters died quickly in an OSR game?

Norman: It'd depend on exactly what had transpired, but encountering monsters that out-power PCs is an important element of old-school play and one that players have to learn how to handle. Clerics are important! There tend to be a lot of undead monsters in old-school play and they tend to be dangerous. Clerics' ability to turn undead, even though it's not always reliable, is invaluable. And if in doubt, use of the fleeing rules in Old-School Essentials is vital!

TWBG: Why did you choose to base Old School Essentials on B/X rather than OD&D or even 5th edition Dungeons & Dragons?

Norman: A mix of reasons really. Firstly, just my personal history. I grew up on Basic/Expert D&D, so I have an ingrained love for and familiarity with that edition of the game. By contrast, I've never played OD&D, so I have no personal connection to it. Another big reason I chose B/X as the base for Old-School Essentials is that I feel B/X has a wonderful balance between simplicity and complexity. For me, and for a lot of other old-school gamers, B/X is a kind of sweet spot between the vaguely defined rules of OD&D and the mechanical complexity of AD&D, and later editions of the game. This is, I feel, probably the reason why B/X and derived games are today more popular than any other type of old-school D&D.

TWBG: Why does the world need another B/X tidy-up when there are already games like Labyrinth Lord, Swords & Wizardry and super easy to reference Black Hack?

Norman: Your question hints at the answer: ease of reference. Looking at the other games that you mentioned, there are, very broadly, two kinds of D&D-esque games that people play in the OSR scene: games that are designed for direct compatibility with an older edition of D&D like Labyrinth Lord, or Swords & Wizardry and games that are inspired by older D&D but that to some degree or another go their own way with the rules, for example, the Black Hack and Knave.

The pro of the first type is of course compatibility: you can pick up an old B/X adventure and run it directly with Labyrinth Lord, for example, with minimal to no conversion. The pro of the second type is innovation, often, as you noted, innovation in terms of presentation and ease of reference. My goal when creating Old-School Essentials was to bring these two things together and create a game that's 100% compatible with B/X while being innovative in its presentation and focus on ease of reference.

B/X itself and other B/X-based games are written and structured in a traditional "wall of text" style. This is fine for fireside reading, but it's not that great for quickly picking out rules in the heat of play. Old-School Essentials structures the rules in a different way. Instead of walls of text, rules are broken down into bullet lists and small paragraphs with headings, making it easy to quickly find what you're looking for. There's also a strong focus on layout, with every chunk of content, be it a rules subsystem, a spell description, or a monster listing, laid out to fit on a single two-page spread.

This really helps usability by minimising page flipping. For example, each character class takes up two pages, including all rules and tables. The rules for dungeon delving, wilderness exploration, and combat are two pages each. And so on. This stuff makes a big difference to referencing a rule book during play, when adrenaline can be running high and no one has time to be reading through big chunks of text.

Also, at the end of the day, in Old-School Essentials, I've created the game that I want to play. I think this is the reason most games or hacks are written. Of course, I'm very happy that a lot of other people want to play Old-School Essentials too.

TWBG: Why stop at X, rather than expanding into the Companion set or even the extremely well-received Immortals box?

I had the Companion and Master boxes as a kid and read through them but in practice I never used them. I recall a grand total of one character in our games who made it beyond 14th level, the maximum level in B/X. I personally see no need to extend B/X with higher levels when almost no one ever gets to that point.

There are also a lot of issues around stretching the character advancement system out into higher levels. Demihuman characters, with the strict level limits they have in B/X, like level 10 for an elf, would either get left behind or would need to be retroactively modified. I'm also not convinced that simply expanding advancement in hit points, attack probabilities, saving throws, etc. actually makes for a good game. So there are no plans for a supplement to extend Old-School Essentials into levels 15 plus. Levels 1-14 cover 99% of what people actually experience in play.

That said, I do think there are some really interesting bits and pieces in the Companion and Master sets. I could certainly imagine an Old-School Essentials supplement adding extra rules subsystems for things like warfare and domain management, for example.

As for the Immortals set, I've never read it as that seemed even more distant of a possibility than getting a character to level 15+! I could definitely imagine that a game focused around immortal PCs could make for a really interesting campaign, though, but would probably want to start characters at that level, rather than requiring them to work through levels 1-36, probably decades of play, as mortals first.

TWBG: OSR games, in general, seem to be very fond of tables, especially random content for the GM. Why is this, and what do you think it adds to play?

Norman: I think there are two main types of tables: those used for inspiration during prep and those used for introducing an element of surprise during play. Both types are very popular among old-school gamers. Prep-oriented tables or generators are amazing tools for spurring creativity, possibly in directions that the individual GM's mind wouldn't normally go. Feeling stuck for ideas about the dungeon you're preparing? There are loads of tables, like those in the AD&D Dungeon Master's Guide, that can be used to come up with ideas for room contents, traps, tricks, etc. Of course, the results of random tables used in this way are best tempered with a dose of judgement on the GM's part, but the results can be very creative indeed. The other type of tables, those for use during play, are favoured by GMs who enjoy improvisation and a sense of discovery or surprise at the table. I'm personally not a big user of tables like this: I tend to be a bit more on the prep-heavy side of things.

I think the reason both types of tables are popular with old-school GMs, though, is at least partly historical. AD&D has tons of tables for all sorts of things, for example, the dungeon stocking tables I mentioned before. There are even precedents in the rules for monster reactions and morale in old-school editions of D&D: the GM is encouraged to randomise monsters' behaviour upon encountering or battling PCs, as a means of modelling the unexpected nature of life.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?