When you love an artist, it’s a wonderful pleasure to slowly work your way through their catalogue,filtering it all through the twin lenses of your own passion and hindsight and charting in your head how they evolved over the course of their career. It’s as true of musicians and directors as it is of painters and sculptors. You’ll linger lovingly over your favourites of course, but the big picture and evolution are what’s really important.

When you love an artist, it’s a wonderful pleasure to slowly work your way through their catalogue,filtering it all through the twin lenses of your own passion and hindsight and charting in your head how they evolved over the course of their career. It’s as true of musicians and directors as it is of painters and sculptors. You’ll linger lovingly over your favourites of course, but the big picture and evolution are what’s really important.

Only recently have we been able to do the same thing for video games, now that the design and programming titans of our youth are nearing retirement age. And it’s not quite the same: so inextricably linked is gaming with the march of technology that you can’t get quite the same pleasure from replaying a classic 8-bit game as you can from a of classical music. But videogame writers still hail their heroes and write fawning biographies.

Board games don’t suffer from the technology trap. Hnefatafl remains engaging now, 1500 or so years after its invention. And analysis and opinion of them certainly has some qualities of art, even if only viewed from the perspective of their social impact or their components. And so when you think about it, it seems quite incredible that no-one bothers to chart the oeuvres of board game designers in the manner so celebrated of artists and designers.

People have favourites, of course. And sometimes you’ll see articles of lists about their design career. But there’s never that all-important overarching sense of progress, change, evolution. Always games are considered for their individual qualities, never for their part in the bigger picture.

In part that could be because there is often no bigger picture. It’s a striking thing about game design that some designers have an astonishingly narrow window on the world. Sometimes they spend their careers tinkering with a single, favoured mechanic, other times it’s a whole system or perhaps a particular theme. In some ways you might imagine a smaller focus might bring out the differences with greater clarity but it doesn’t seem to work that way. Rather there’s a sense of frustrated invention about things, repeatedly coming from different angles toward the same ends but never quite realising the goal.

It’s also a function, I’m sure, of the fact that many game designers are part-time and so never develop the body of work necessary for wider judgement. But there are designers who escape all these charges, and end up with a catalogue that’s widely varied and yet offers a sense of individual style. Often they’re amongst the most famous designers: Friedemann Friese, Reiner Knizia, Vlaada Chvátil, Rob Daviau. Why is no-one writing biographies of their work?

That has to be down to one of three things. The first two are related: a lack of vision or interest amongst board game writers or readers. The third is simply that there’s value in overviews of this kind when it comes to board game design.

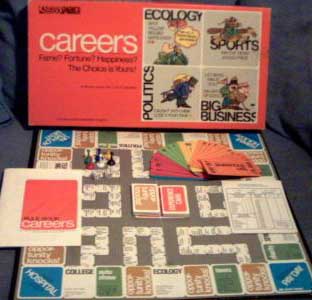

Let’s consider that for a moment. I’m firmly of the opinion that the recent history of modern game design can be seen as a series of incremental improvements as designers learn from previous mistakes and successes. The corollary of this - that on the whole games are better and more interesting than they were 40 years ago - seems self-evidently true. The whole period can be seen as a gradual evolution. In this context, the work of seminal designers like Sid Sackson, for example, should certainly be seen as being of pivotal importance. So I think we can reject the idea that there’s no value in retrospectives pretty much out of hand.

So that brings us back to writers and their readers. When examining that sort of relationship I don’t feel you can really blame the readers. It’s not their job to come up with interesting new formats. A lot of them probably don’t really know what they want to see until they read it. No, the fault here is with the journalists themselves. With me.

And that of course begs the question of why I’m writing a whole article about the lack of a format rather than just doing a career retrospective myself. The answer to which should also answer why it’s not something we see more often. Namely that it is extremely hard work.

When you read an overview of the work of a painter or a musician, in most cases their work can be fitted fairly clearly into the whole overview of the art in question. The benefit of hindsight helps hugely. You don’t have to know much about music to realise, for instance, the pivotal role Led Zeppelin played in the development of heavy metal the first time your hear their songs.

With existing art forms there’s also a big body of existing work that you can draw on to fill gaps in your knowledge. Other writers, fans, random lunatics have already contributed a mixture of dross and valuable insight to the cause. If you need inspiration, or just information, all you have to do is wade through the rubbish in search of the gems and you’ll get what you need.

Neither of these luxuries is afforded to the board game writer. The sector is simply too small. You can’t always find useful work by forebears to draw on, and you can’t see the bridges between the work of different designers because the talent pool is too limited, and the mechanical options too restrictive. If you want to write a career retrospective, you’re the trailblazer, seeking out the connections from the ground up.

Video gaming is a young hobby, and the pioneers who started talking about the way the work of designers fitted into the grand scheme of things had to work just as hard. But they’ve done their part now, and the format has reached the critical mass necessary for those sorts of things to become more and more common. Board gaming, we’re still waiting for the first steps on that frontier. Whether we’ll get them without a paid profession base to put the hours in remains to be seen.