I just bought Middle Earth Quest, which is a good example of a species of boardgame that I'll call the clockwork game. It's worth noting the existence of this part of our hobby, since it represents some of the best and worst aspects of game design.

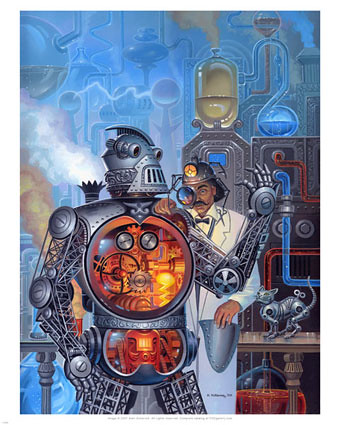

A clockwork game has several distinct, specialized mechanics that have a largely indirect impact on each other. You can think of each mechanic as a gear in the larger machine: Each turns on its own axis, but they're designed to have an effect on each other's motion.

How clockwork games work

War of the Ring is a good example of a clockwork game. The two primary gears of the game, the military struggle for Middle Earth, and the quest to destroy or capture the One Ring, are distinct, but not completely separate. The overall machinery of the game won't work in your favor if you power, lubricate, and monitor one gear over the other. The obvious reason why the single-gear strategy won't work is the opportunity you give your opponent to win a quick, easy victory on the neglected front.

The less obvious reason why the single-gear strategy doesn't work lies in the other moving parts of the game. The action dice make the pool of available actions unpredictable. If you bank completely on a military victory, the action dice might not get the opportunity to recruit and attack at critical points in the game. The Free Peoples face another problem, activating nations, that forces choices in how you use the heroes gear.

An even better example of a clockwork game is Twilight Imperium. At the same time, you need to be juggling research, military build-up, political influence, expansion, and defense, while keeping a careful eye on how the victory conditions evolve. That's a lot of separate but interlocking gears, which makes Twilight Imperium either a fascinating or maddening game, depending on your tastes.

Clockwork games have a long lineage. Civilization certainly is an ancestor, with its simultaneously spinning gears for expansion, city building, trade, and research (advancements). Magic Realm is, arguably, another, since you're trying to make the overall machinery that combines exploration, combat, character advancement, and inventory management, and readiness.

The reason for clockwork games

Clockwork games have two main attractions:

Strategic depth.One of the easiest way to increase replayability is to add different mechanical components. Not only do you need to master how each component works, but you can also experiment with different strategies to optimize the interactions among these components. Starcraftprovides these kinds of options.

Simulation.Games, by necessity, must convert complexity into abstraction. If you are trying to simulate something in the real world, such as WWI, you can reduce the details too far, making the outcomes unrealistic. If you are trying to simulate a complex fiction, such as the Lord of the Rings novels, you can reduce complexity do the point where you lose the surrogate experience that the game is supposed to re-create.

These two rationales for building clockwork games also become the standards by which you judge them. How many plays is Warrior Knights worth? Does Sword of Rome do justice to the historical topic? Does Marvel Heroes give you the feeling of playing out several issues' worth of comic book plots?

If Fantasy Flight Games appears frequently on the list of examples, it's because their licensing successes make it important to simulate the intellectual property that they've licensed. Battlestar Galactica would have been a far less interesting game without the traitor mechanic, or space combat, or the challenges of scraping by with limited (and dwindling) resources.

When the gears fly apart

When clockwork games fall short, it's usually because the whole is not greater than the sum of its parts. Creating different gears for each aspect of the game does not mean that the gears mesh with one another well. Nor is it inevitable that the overall experience will be satisfying. An analogy might be the difference between a WWII encyclopedia and any decent narrative history of the war: while the former depicts all the informational components, the other needs to provide many of the same components, plus make them work together to tell the overall history of WWII. You could piece together the narrative of the conflict from the encyclopedia, but it won't be easy, or all that interesting.

Sorry to beat up on Age of Conan again, but it's a prime example of a clockwork game that doesn't quite work. The root problem is its lack of clarity over what exactly it's depicting. If the real focus is the clash among Hyborian kingdoms, the Conan adventure mechanic is superfluous. Nexus/Fantasy Flight clearly thought that it wouldn't be a good Conan game without Conan slaying oversized snakes and squeezing the backsides of bar wenches, but the vague and flavorless "Gimme one of them adventure tile thingies" mechanic doesn't do justice to the story of Conan, and they're not obviously needed for Aquilonia and Turan to go to war.

Many have bemoaned the problems creating the great dungeon crawl game. There's a big menu of complaints about the attempts such far, such as length (Descent), blandness (Prophecy), randomness (Dungeonquest), and sheer clunkiness (Tomb). What makes the perfect dungeon crawl game an elusive objective, however, is the lack of focus. If you're trying to tell an epic story about defeating an evil overlord, some of the conventions of this genre, such as character advancement, aren't necessary. If you're trying to re-create just the monster-killing, treasure-hunting aspects of the genre, then "levelling" can be very important, as players race to meeting a quota of monsters killed and artifacts collected.

In other words, the machinery of a dungeon crawl game, which is inherently a clockwork game, is designed for a particular purpose. The choice of gears, therefore, is largely a question of whether they're needed for that purpose or not. The performance of the machine overall is also a consideration: Descent is a very well-designed game for what it's supposed to do, but it takes a long time to play it. (So long, in fact, that it begs the question, "Why aren't we playing D&D?")

I like clockwork games. Many of my favorite titles (Twilight Imperium, Sword of Rome, etc.) are clockwork games. However, I've reached a point when I open the box of a game like Middle Earth Quest, look at all the decks, tokens, stand-up counters, plastic minis, and special symbols on the map, and I think, "Hmmm, is this going to be another Age of Conan?"