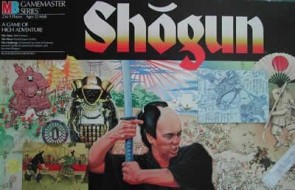

Possibly the best of the Gamemaster series, Shogun has lasted down through the decades because of a solid foundation.

Milton Bradley's Gamemaster series of Axis and Allies, Broadsides and Boarding Parties, Conquest of the Empire, Fortress America, and Shogun (which is how I'll be referring to it from here on out, since that was the original name) has passed into gamer legend. It was the first effort by a major, mainstream game company to create wargames that were not only quite solid in design, but also were far more elaborate in production than most others of that ilk; the most notable competitor being Avalon Hill, which released almost strictly hex-and-counter games with far more complexity and far lower component quality. The Gamemaster series not only used recognizable maps with actual detail (as opposed to the oddly-segmented, colored blobs of Risk), but produced miniatures that were superior in quality to the pawns or figures of almost any other MB release. This was the advent of "specialist games", long before Games Workshop used the label. The Gamemaster series touched on five different historical periods and a variety of different cultures and scenarios and did an extraordinary treatment of at least three of them by a company mostly known for mass produced, mainstream fare like The Game of Life, Twister, and Candy Land. They were aiming for a market a long way from Battleship or a barely-designed IP paste-on of the latest hit movie or TV show. And Shogun was probably the best of the series.

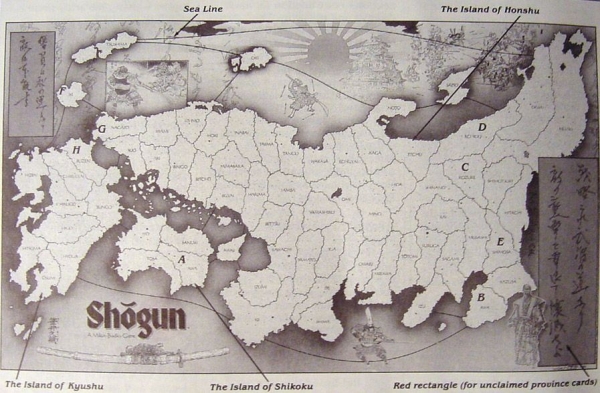

Shogun is set in feudal Japan, representing the civil wars of the Sengoku period where different clans were trying to be declared master of all Japan in the name of the emperor; a conflict eventually won by the Tokugawa clan that would rule Japan for the next 268 years. In addition to the literal pile of decently-sculpted miniatures that came with the game, the player "boards" were Styrofoam shaped to resemble Japanese fortresses, and the dice used for combat were d12s. You would have been hard pressed to find anyone in 1984 outside of regular RPGers (aka D&D players, mostly) who would've known what a d12 was, and that included hardcore wargaming nerds like those who played Avalon Hill's output, which used almost exclusively your regular six-sided dice that you see on a craps table. Indeed, the other four games in the series also stuck exclusively to regular, old d6s. This seems to hearken back to the long-time Games Workshop assertion that using d6s was not only easy for players, who could find them in other games or simply buy them at stores in the 1980s, but was also cheaper for game publishers, since they could be easily mass produced. But here was a game that used d12s, which wasn't even a common die for most RPGs, for a not especially complex but perfectly interesting combat system.

Truly, this game and the series as a whole were a very odd duck on the shelves at the time. Axis and Allies lasted from that point forward, with multiple editions and expansions. Fortress America had one uneasily received reprint in 2012. Conquest, similarly, had one reprint in 2005, while Broadsides, sadly, faded from view shortly after release. Shogun, however, soldiered on somewhat like A&A, with a re-release in 1995 as Samurai Swords and then a subsequent reprint in 2011 as Ikusa. Unlike Fortress or Conquest, the rules for Shogun have not changed through subsequent editions. It still uses d12s and it's still pretty straightforward in application. If you're looking for cultural flavor, this game won't really light your fire. But if you're looking for a solid, strategic, and often elegant wargame, you've found it.

One of the central mechanics to Shogun is the bidding/spending phase. At the end of each round, each player generates koku based on the number of provinces they own. In the following round, they assign their koku to five different options, two of which are a bid for control and the other three being the more typical building options (troops, fortresses, etc.) The system isn't too far outside the norm of most area control games, wherein the more area you control, the more resources you have, and the more dudes you can buy. This has been typical since Risk. But the two bids for control- of turn order (swords) and the ninja -are what bring real tension to that phase. Unlike most area control games, where turn order is procedural (moves clockwise around the table) or determined by board factors (whoever controls x amount of territory, etc.), in Shogun you can dump as much money as you want into the bid for taking whatever place in the turn order that you like. That becomes important because the key to success on the battlefield is directly reflected in the ability of your three daimyo. The more they win, the farther they can move, and the more battles they can fight. Get yourself a maxed-out daimyo in the late game and he can tear across half of Honshu and beat down your opponents singlehandedly. And that's where the ninja comes in...

As with most wargames, you want to spend your resources efficiently. No one wants to be spending on things that don't directly contribute to the war effort, be it long-term (often technology in games like Twilight Imperium) or short-term (more dudes!) But you have to give some consideration to "throwing away" your koku on the ninja if only to prevent your opponent from hiring him and having a 66% chance to knock off your experienced daimyo with one die roll. Your Datsun Z (dating myself) that could tear across three provinces and fight everyone within sight? Yeah. He's now just a pedestrian like the rest of us and can only hassle the neighbors. He's gone from Oda Nobunaga to some guy with a cool banner. Sure, you could hire the ninja for his other purpose, which is to spy on an opponent's money allocation before selecting your own. It might even be wise. But it's just not as viscerally pleasing as chopping the head off the snake. (And, no, let's not talk about the fact that, if you fail, the ninja can be turned against you.)

But the other thing to consider in this, again, often elegant game is the part of the build phase that draws from the historical reality. Resources were often scarce in Japan and there wasn't enough food or metal to go around to raise armies in the way that Western societies often could. When you dump a bunch of koku into making more dudes, you can only assign one dude per province. This isn't like those games where you build up the cash and then create the Spanish Armada in a single port and use it like a sledgehammer. You have to build up control and use your armies more like scalpels, since they'll be growing slowly and generally only when you can swoop through other provinces and conscript the locals. Or you can just do what a lot of generals did when they had more cash than men and hire mercenaries.

Ronin were a fact of life during the Sengoku and following Edo periods. With so much warfare, local lords were dying left and right (or being stripped of their titles; just as bad) and there were samurai who became separated from the anchors of their existence. The best thing about them is that they are, again, still samurai and that's reflected in their combat ability (i.e. it's better than peasant spearmen.) On top of being able to recruit a number of them and dump them into whichever provinces you like, you also do so secretly. Everyone can see where you're building up your regular troops and your army compositions are never a secret. But ronin just kind of appear from the ether if your enemy steps into the wrong marketplace. It's a scene out of Seven Samurai every time. The downside, of course, is that they're mercenaries, which means they don't stick around after the job is done and you just have to pay them again, like real people. The nerve!

But one of the best parts about Shogun is what was a quite innovative combat system for the time. Other games had both initiative-based combat (where the faster guys get their hits in first) and differences in skill determined by die rolls (the aforementioned ronin hit on 5s, as opposed to the ashigaru spearmen, who hit on 4s), but most didn't combine those approaches with a completely separate casualty phase for ranged combat. Your ronin are cool and all, but if my force is largely samurai bowmen and ashigaru gunners (the introduction of the musket having been a key element to what kicked off the warring clans period) who shoot and remove the enemy before your guys can lift a katana...? Good luck. There's always been something to be said for the equivalent of human wave attacks or Zerging in wargames, since you can just throw dudes (bodies) at the enemy until you wear them down. But in this system, it's entirely possible that your sea of bodies could be utterly neutered before you lifted a finger. That meant trying to achieve one of many balances: Between fueling mobile armies and crucial static defense; between expensive fast hitters and numerous slow ones; between spending money on the things that matter (dudes, forts) and those that might matter, if you could make them count. It's a smart design and it contains more depth than many people expect on their first play.

What is it lacking? Well, maybe a lot of the cultural character and/or chrome that we've come to expect from modern games like this? There are no "variable player powers." Everyone is doing the same thing with the same dudes. There are no environmental effects or events (although there is a nice event/strategy card system that someone posted years ago on BGG.) Variability in the game is contained solely in the dice that you roll and the decisions that you make, which is a point of attraction for many wargamers that I know, but less so for many others who tend to like their games to tell a story, even the ones about conquering the board and wiping out the opposition. This also isn't a game that you'd play if you wanted to immerse yourself in Japanese culture. Other than the map on the board and the obvious unit names (daimyo, samurai, ashigaru, etc.), there's nothing here that wouldn't fit in another environment with different names and a different map. In that respect, it's clear that it's a game that's 35 years old. That said, I would recommend that everyone I know who's interested in wargames at least try it, not only for the elegance of the mechanics, but also because there's not much detail to get bogged down in. There's not much to remember because the game asks the players to provide the context of how the game flows, much like abstracts such as chess. In most respects, Shogun has turned out similarly to be a lasting treasure.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?